Charlie Chaplin is among the most beloved figures in film history, so it may come as a surprise that there was a period when public sentiment in the United States largely turned against him. Beginning in the early 1940s, Chaplin experienced a litany of personal and professional setbacks that included a bogus paternity lawsuit, an indictment under the Mann Act, an investigation by the House Committee on Un-American Activities and poor public reception of his films. In 1952, following Chaplin’s departure for a visit to Europe with his family, the U. S. attorney general effectively barred Chaplin from returning to the United States by revoking his re-entry permit. During this period, Chaplin could find few friends in Hollywood and even fewer in the press, except for Harry Crocker.

Harry Crocker was the heir apparent to a prominent San Francisco family that had its wealth entwined with the first transcontinental railroad. While he could have been contented to bask in his family legacy and fortune, he looked to the film industry to explore his own identity and find purpose. Throughout his lifetime, he would wear many hats that included acting in, directing and writing a number of classic films before ultimately finding his niche as an entertainment reporter for Hearst publications.

Crocker attended Yale University where he studied law, but his inclinations always pointed toward entertainment. After appearing in a number of stage musicals, he ventured to Hollywood in 1924 and ended up at MGM. From the time he arrived in Hollywood, the affable Crocker had little difficulty finding work and making friends. He first played bit parts in two King Vidor films: The Big Parade with John Gilbert and the Lillian Gish vehicle La Bohème. His next appearance was in Tillie the Toiler starring Marion Davies, with whom Crocker became close friends. Crocker also began a friendship with Davies’ paramour, William Randolph Hearst, who would provide Crocker with what ultimately became his legacy, the syndicated column “Behind the Makeup.”

“Behind the Makeup” first ran in 1928 and, unlike the column written by his Hearst publications peer Louella Parsons, Crocker chose to avoid gossip and focus more on business developments in the industry. Crocker eventually drifted away from the production side of film altogether in favor of his career as a writer. He penned “Behind the Makeup” until 1951 and wrote several books about Hollywood, including a substantial biography of the man who had stirred his imagination and inspired his creativity: Charlie Chaplin.

In the latter half of the 1920s, Crocker met Chaplin and soon found himself serving as Chaplin’s assistant director on his 1928 classic, The Circus, as well as being cast as Rex the tightrope walker. Shortly after that production wrapped, Chaplin called upon Crocker to serve as his assistant director again (in addition to uncredited roles as writer and publicist) for 1931’s City Lights. Despite having a falling out during production of City Lights, Crocker and Chaplin resumed their friendship, with Crocker eventually working as a unit publicist on both Monsieur Verdoux and Limelight. Crocker also struck up friendships with two of Chaplin’s wives, actress Paulette Goddard (whom he divorced in 1942), and his widow, Oona O’Neill Chaplin. Crocker’s admiration for Chaplin ran so deep that he dedicated his first book to the cinematic icon, although the volume was never published.

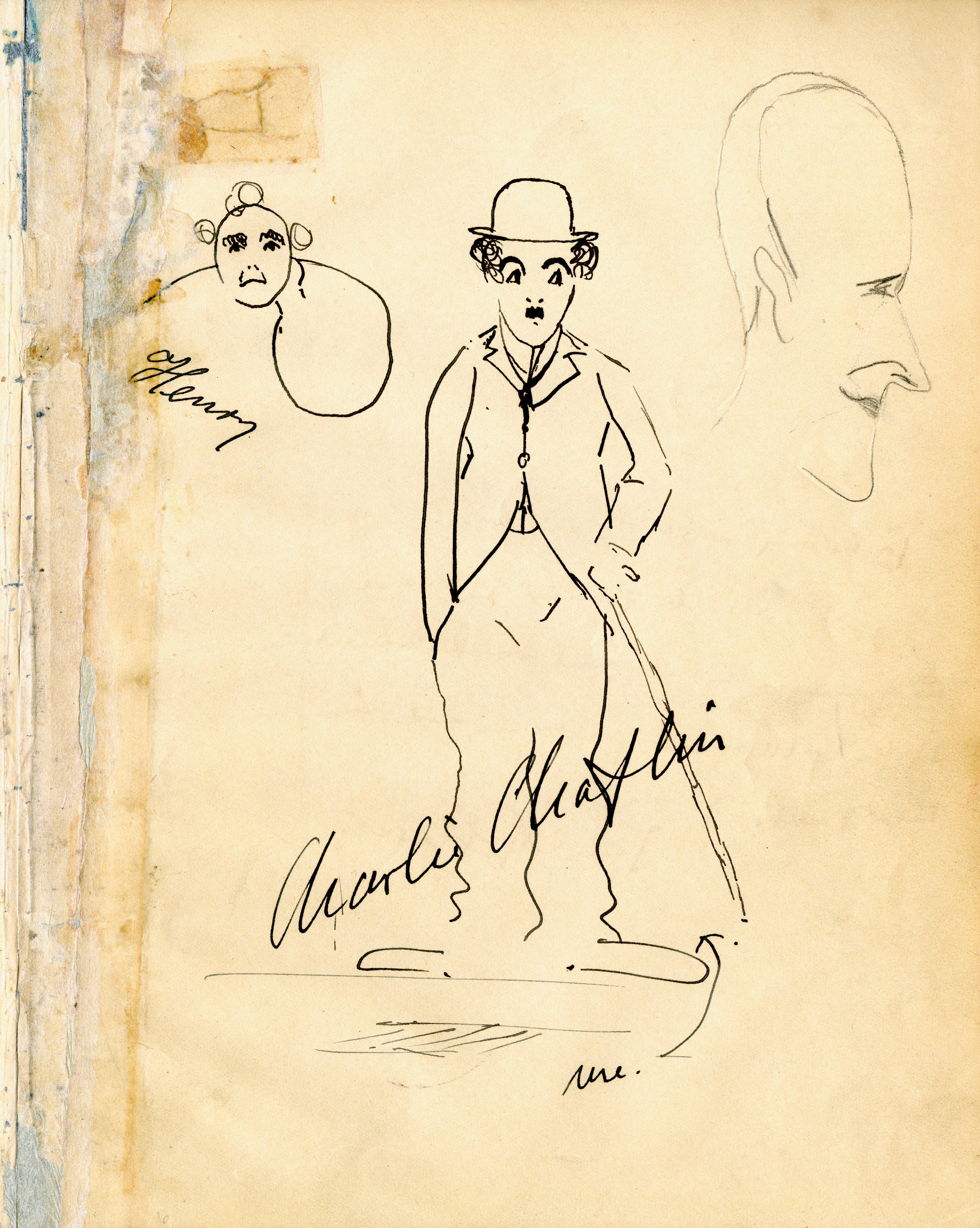

In the 1950s Crocker began and finished a book that was devoted exclusively to the subject of Chaplin entitled Charlie Chaplin: Man and Mime. Divided in two parts, the first half examines Chaplin’s childhood while the second half explores Crocker’s personal experiences working with Chaplin on The Circus and City Lights. The manuscript is rich with first-hand details of Chaplin’s creative genius at work as well as his explosive temperament; it provides a very sympathetic but even portrait of a man Crocker truly admired.

As public sentiment turned away from Chaplin and he was barred from returning to the United States, Crocker saw fit to write an addendum to his manuscript that served as a defense of his friend. Crocker recalled how he tried to help: “Chaplin was in a pickle of unpopularity, and, while I felt that it would be impossible for me to make him popular overnight, I might, through my twenty-one years as a newspaper man and through my immense number of friends in the newspaper field, succeed in doing some good.” The manuscript was never published, however, and Crocker passed away in 1958 before seeing Chaplin restored to public favor in the U.S.

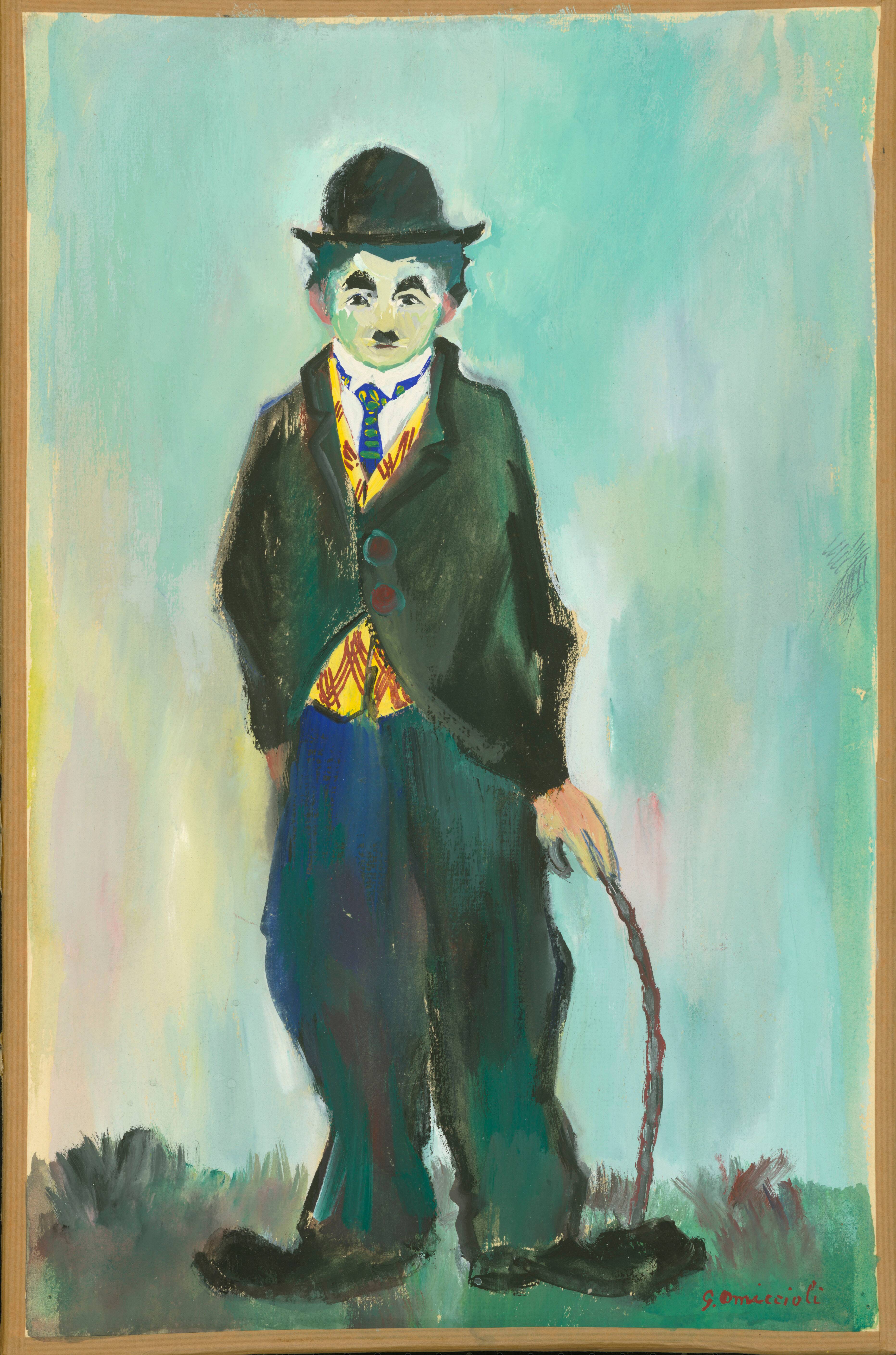

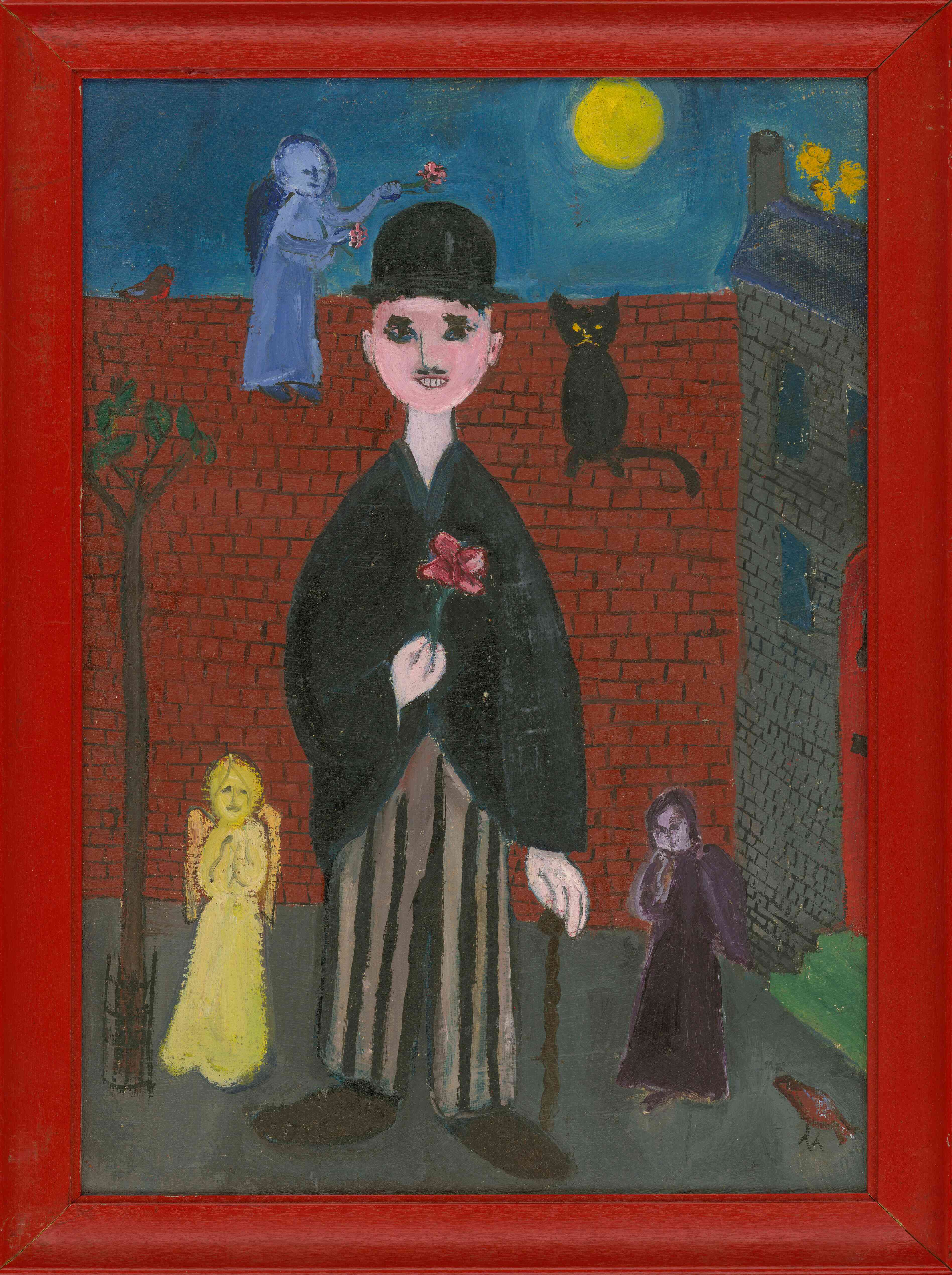

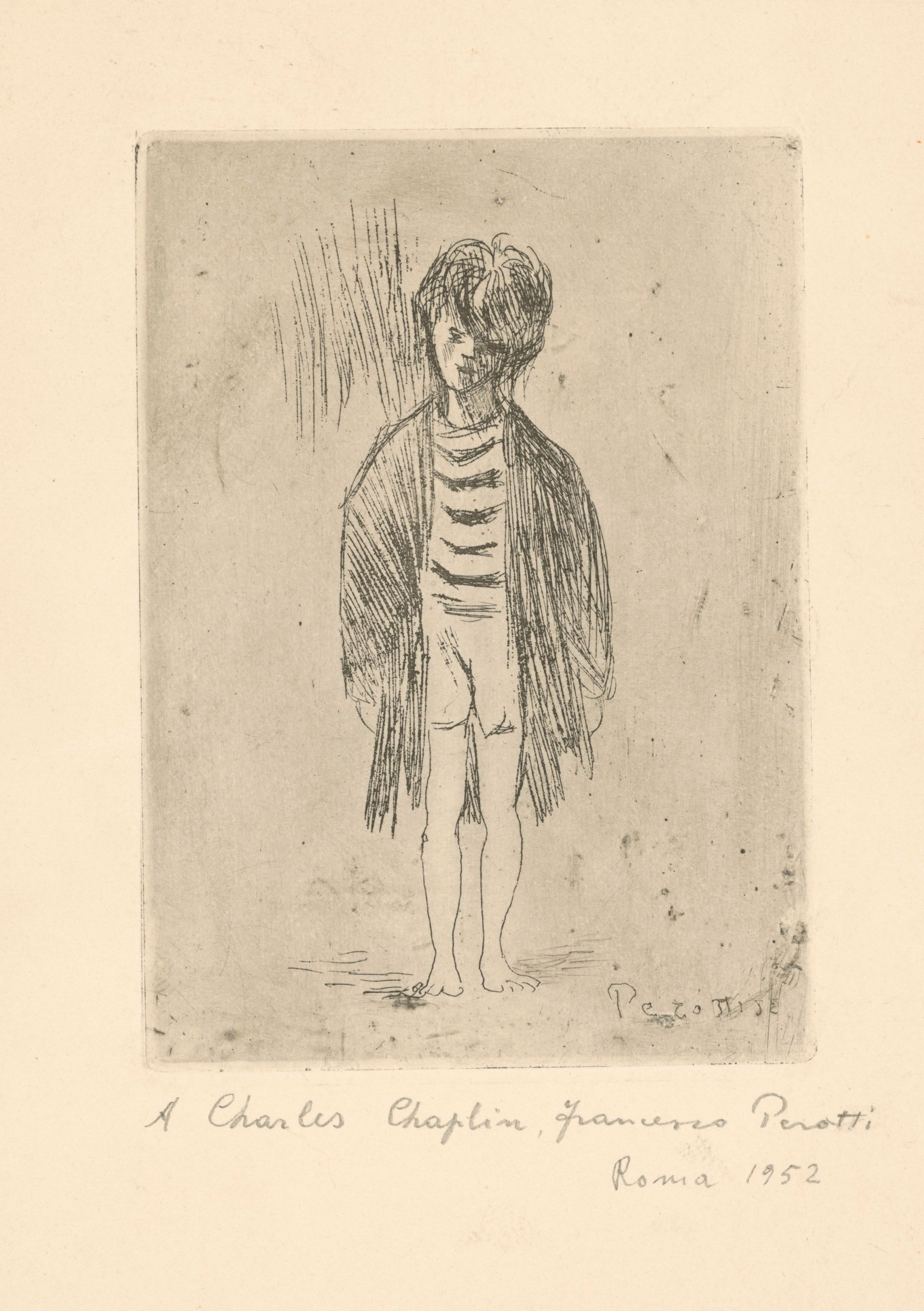

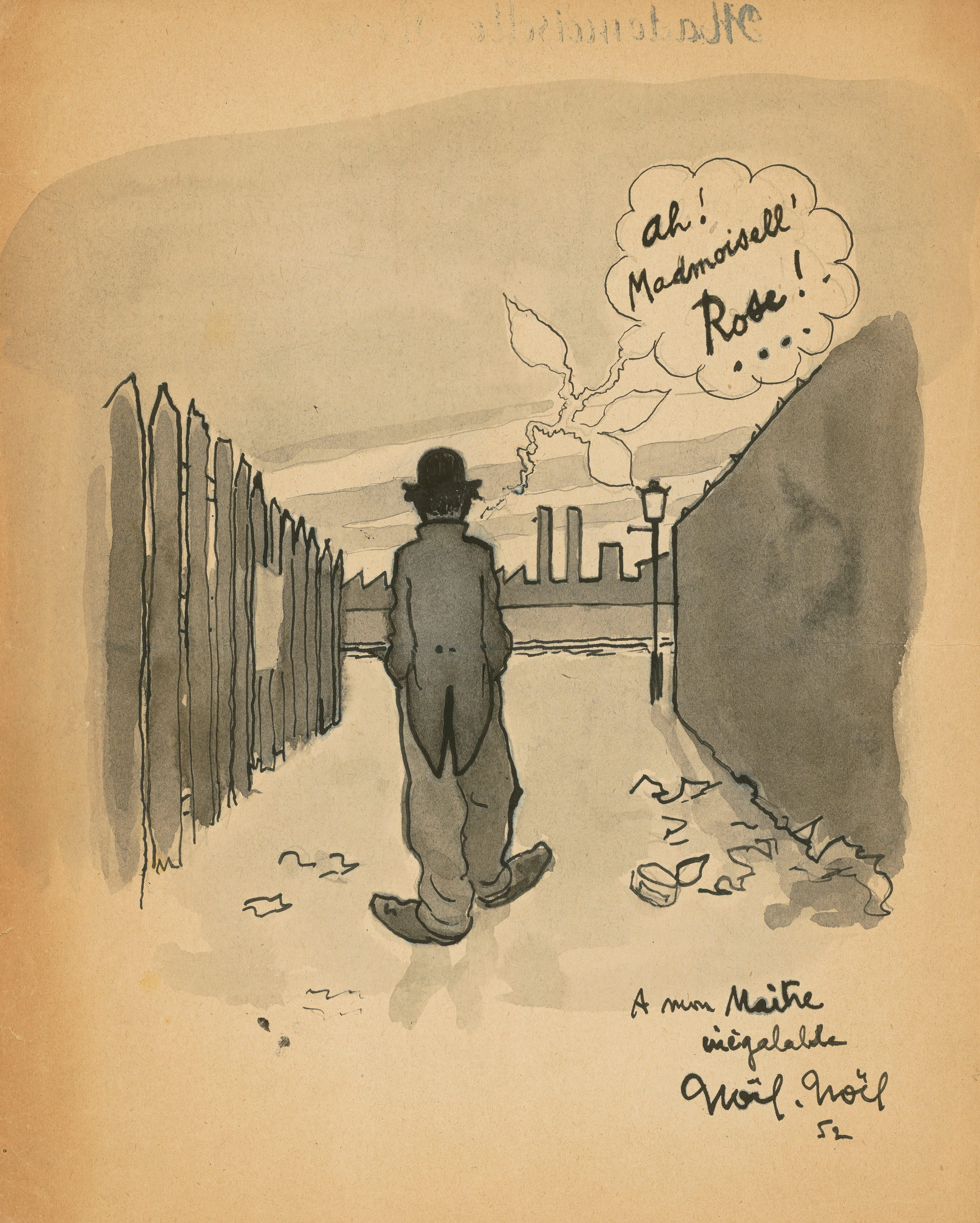

In the process of writing Charlie Chaplin: Man and Mime, Harry Crocker accumulated an array of research material that fueled his writing and allowed him to bring the story to life. This material, which includes manuscripts, drawings and more, is part of the Margaret Herrick Library’s Harry Crocker papers and can be viewed here.