When Philadelphia-based publisher J.B. Lippincott Company decided to publish Harper Lee’s debut novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, the company requested an initial print run of just 5,000 copies. Nevertheless, upon its release in July 1960, the novel swiftly gained popularity and earned a place on the New York Times bestseller list. Unusual for a promising literary property, the motion picture rights to which were often sold before publication, To Kill a Mockingbird spent six weeks on the list before producer Alan J. Pakula and director Robert Mulligan acquired the rights to the book, which would go on to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1961.

Once they had purchased the property, the little-known filmmakers quickly realized they would need a major star in order to move the project forward in Hollywood. They approached Gregory Peck about the role of Atticus Finch and he immediately accepted. With Peck’s participation assured, his company, Brentwood Productions, financed the picture and Universal signed on to distribute it. Soon thereafter, the filmmakers sought out playwright Horton Foote to write the screenplay. As pre-production proceeded, Pakula and Mulligan attracted other talented artists to the project, including cinematographer Russell Harlan, composer Elmer Bernstein and production designers Alexander Golitzen and Henry Bumstead.

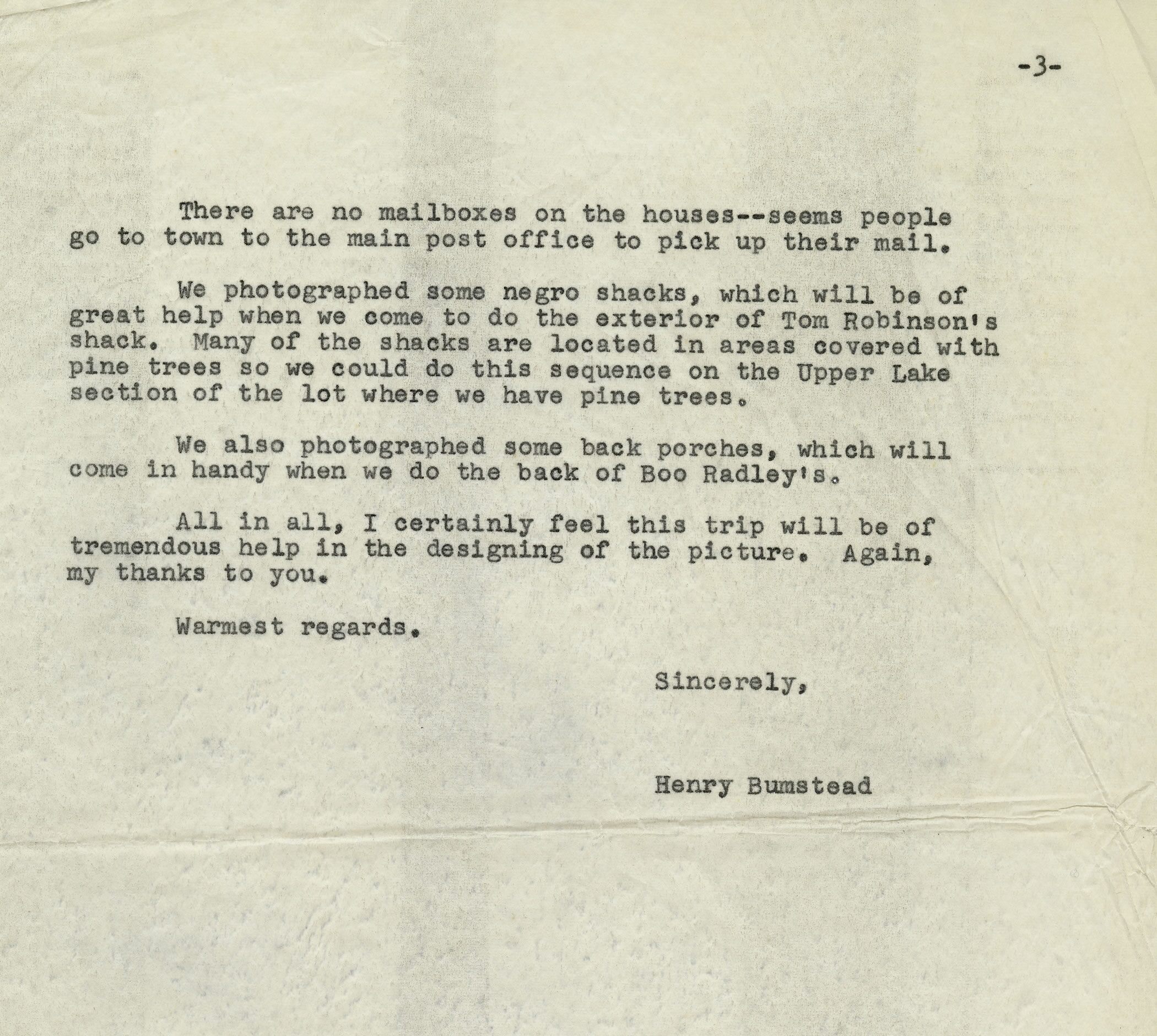

In order to serve the story justly, Pakula and Mulligan were also keen to involve author Harper Lee in the project. In November 1961, the filmmakers sent Henry Bumstead on a research visit to Monroeville, Alabama. As Bumstead’s letter to Pakula below indicates, Lee welcomed the art director to her hometown and accompanied him throughout his visit, offering suggestions about how the architectural and design details of the novel’s fictional community of Maycomb could be most accurately portrayed in the film. Pakula also asked Lee to obtain photographs of Monroeville in the 1930s on their behalf, adding: “We could take the easy way and just stick Atticus and the family in a nice, new ranch house and give the Radleys a big, new picture window for Boo to look through, but somehow I don’t see the picture quite that way.” Bumstead worked closely with the craftsmen at Universal to recreate the Southern locale on the studio backlot and even replicated the Monroeville courthouse. Lee, pictured here with Bumstead, was astonished by how accurately the filmmakers had reproduced a Depression-era Southern town when she visited the studio.

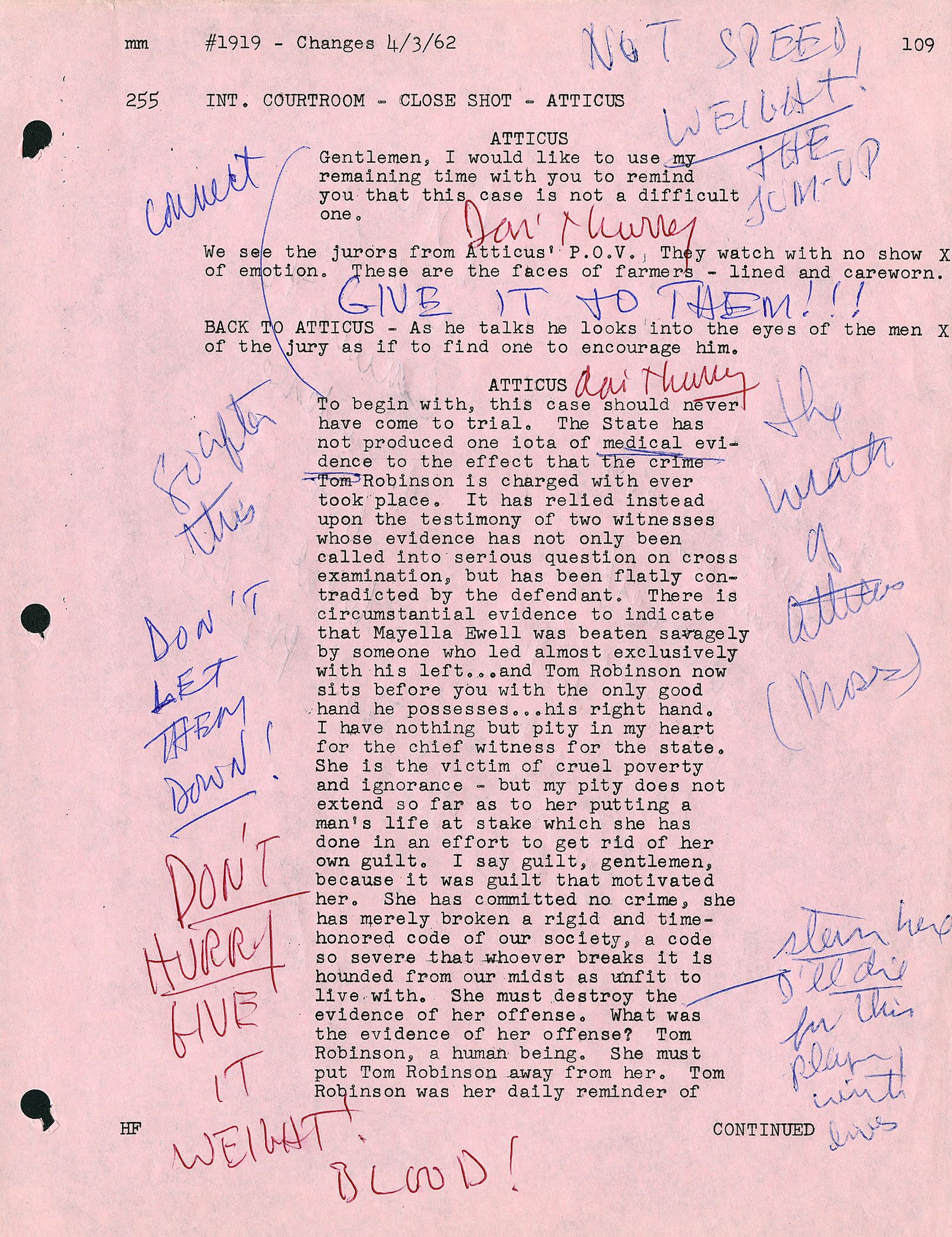

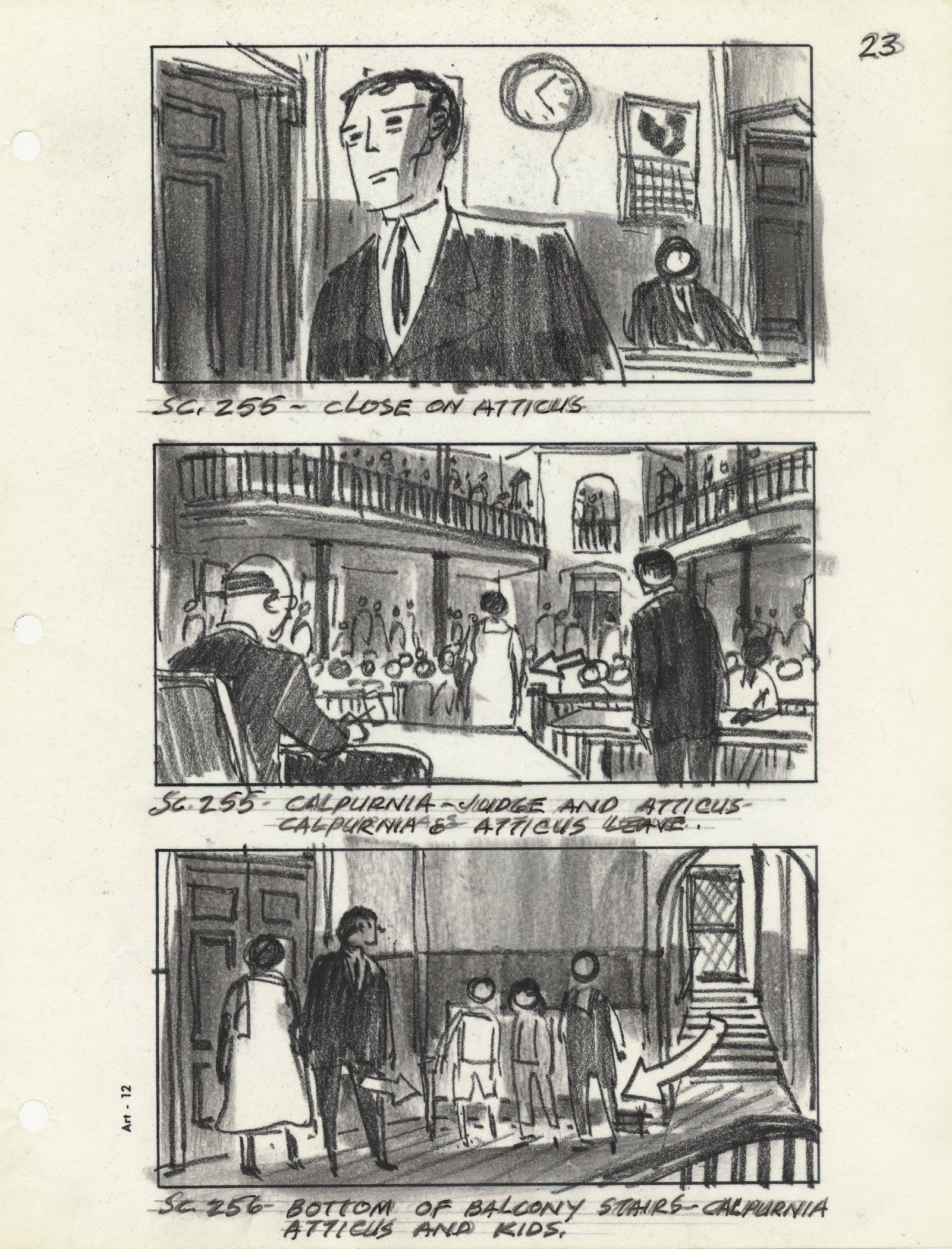

Gregory Peck, whose character was based upon Harper Lee’s father, also went to great lengths to ensure his portrayal did justice to Lee’s creation. He visited Monroeville and was introduced to her father, Amasa Coleman Lee, from whom he drew inspiration for his role. Peck worked hard to develop his character and made extensive notes about how he envisioned playing each scene. This page from Peck’s shooting script shows his notations for the dramatic courtroom scene, which is depicted below in storyboard form.

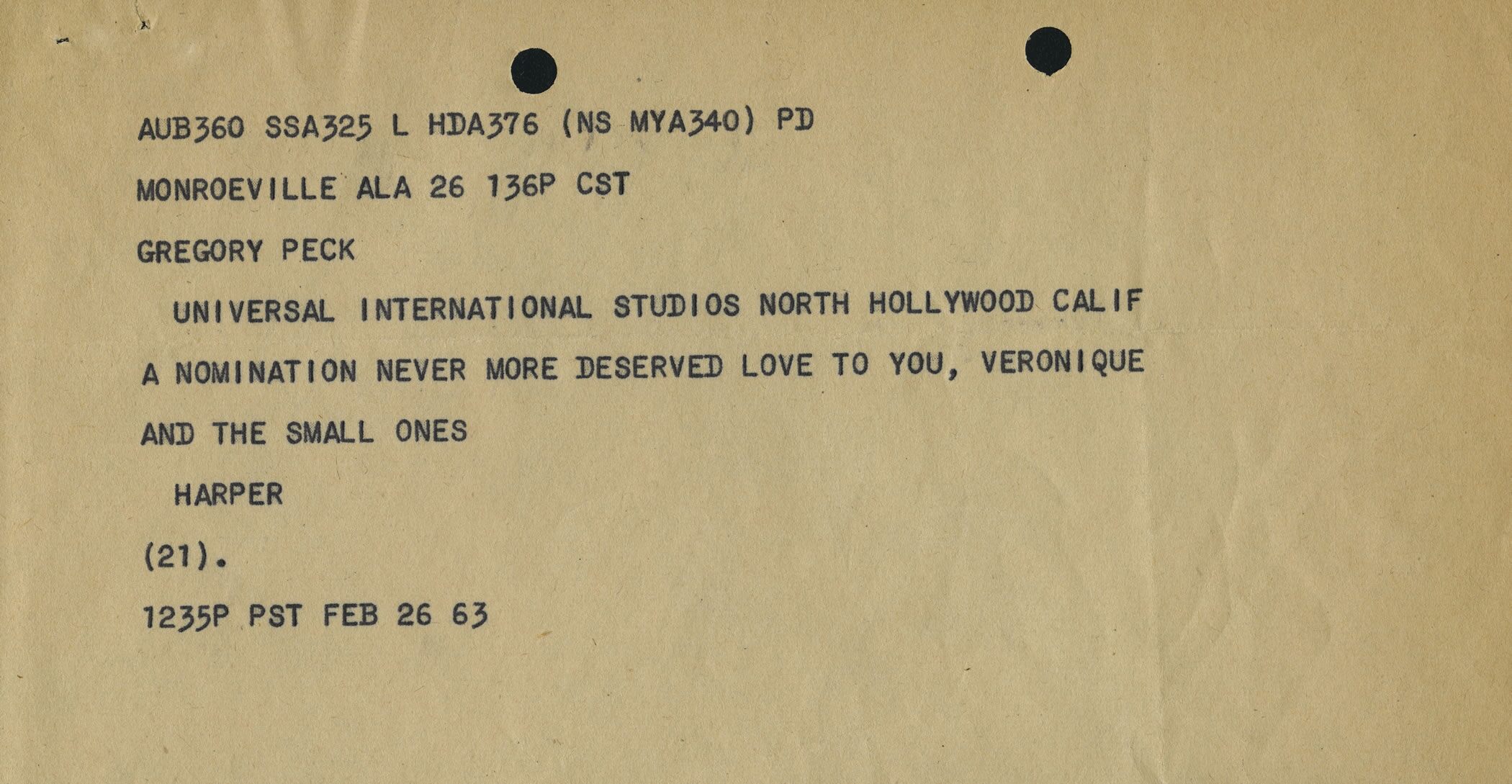

Harper Lee and Gregory Peck became lifelong friends as a result of their collaboration on the film. Lee was one of his most enthusiastic supporters when his performance was nominated for an Academy Award, and she was equally thrilled when he took home the award for Actor in a Leading Role. In turn, Peck shared the accolades for the film with Lee, declaring in a March 1963 letter to her: “Congratulations on your eight nominations for the Academy Award.”

In all, the film earned three awards from the eight nominations, and has become a much-beloved classic in the American film canon. Material regarding To Kill a Mockingbird can be found among several Special Collections housed at the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, including the papers of Henry Bumstead, Alan J. Pakula, Gregory Peck and Robert Mulligan.